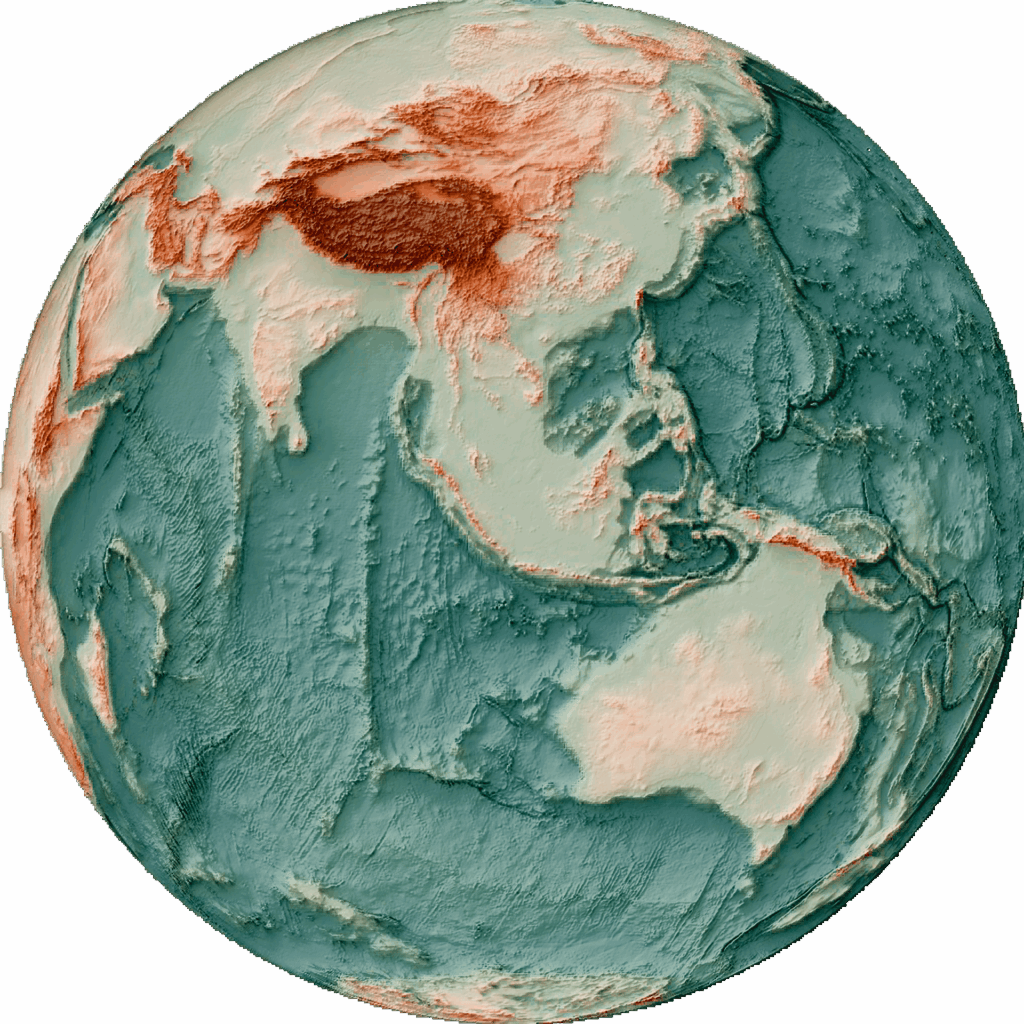

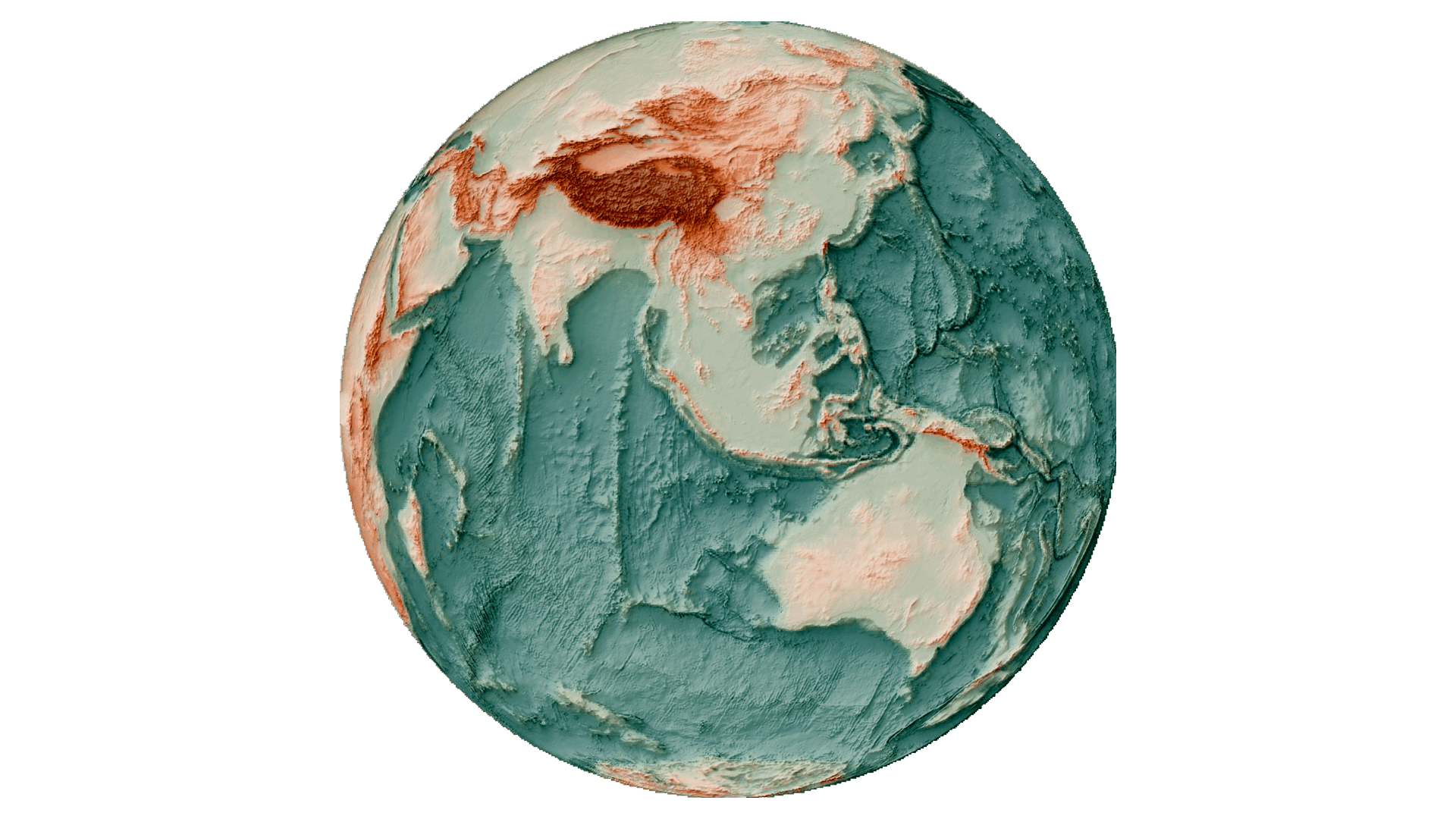

If you are asked to find out what the climate used to be like hundreds of thousands of years ago on Earth, where do you think you would go? Surprisingly enough, one of the best answers to this question is down at the bottom of the ocean. The ocean floor is not just a barren place devoid of life; it is one of the richest natural archives of Earth’s climatic and environmental history.

Grain upon grain, the bottom of the ocean gathers an unending quantity of dead plankton residue, volcanic ash, river and glacier mud, other chemical mixtures, and so on. It goes on slowly, over thousands, even millions, of years. These things slowly accumulate, differing in distinct layers. These layers are like natural archives and a column of it can be extracted which geoscientists refer to as sediment cores. These sediment cores are like the “black box” of the Earth – storing minute history of the Earth’s weather and climatic conditions over millions of years.

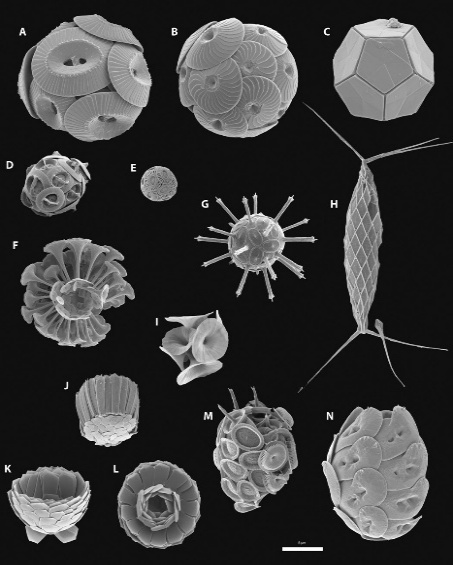

In every layer of these sediment cores, microorganisms like foraminifera, diatoms, and coccolithophores are embedded. These microorganisms had shells made of calcium carbonate or silica. By examining the chemical composition of these fossilized shells, scientists can estimate:

- The ocean’s and the continent’s temperature at that point

- When ice ages occurred and if ice covered the Earth

- Shifts in ocean salinity and pH level

- Productivity of the ocean’s ecosystem

This makes microfossils more than just leftovers from ancient life; they are like tiny climate reporters. Their shells hold chemical clues that tell us a lot about what the environment was like when they were alive.

That gives researchers the condition of Earth at one point in time. But how do researchers connect this to a specific point in history? There are many ways to do this.

The ratio of some isotopes – such as Oxygen-18 and Oxygen-16 – in the Earth’s atmosphere have changed over the millions of years of the Earth’s existence and we know how it has changed. Organisms on Earth absorb these and the isotopes become a part of them. Armed with that information, researchers can measure the amount of different isotopes found in these microfossils. By correlating the two, researchers can estimate the age of fossils and therefore, the age of a layer in a sediment core.

Sometimes, the fossil itself can indicate the age of the sediment layer. Creatures such as Trilobites, Ammonites, Graptolites etc. fossils are abundant in marine environments and we know when they existed. From this, we can easily tell how old a sediment layer is from the fossils they contain. Fossils like these are called index fossils.

Besides isotopes and index fossils, researchers also use magnetostratigraphy which is basically a record of Earth’s magnetic field reversals preserved in sediments. By combining all these methods, they turn a boring looking sediment core into a super accurate timeline of Earth’s history.

Here are some things we’ve learned from sediment cores

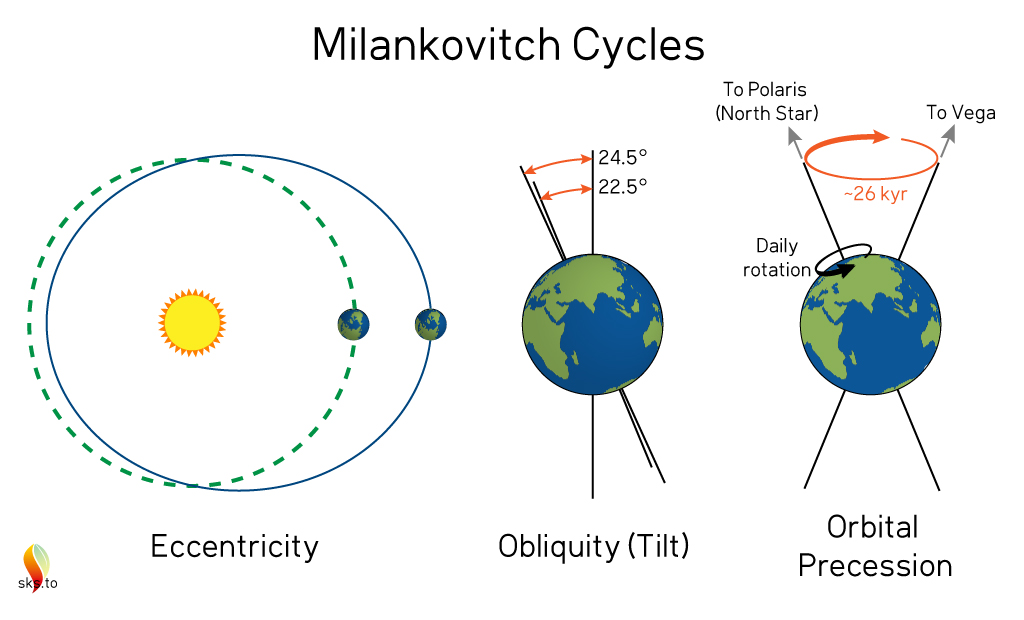

1. The Return of the Ice Ages

Sedimentary core studies establish that the world has experienced recurring episodes of ice ages and interglacial warm periods. Behind the changes lies the Milankovitch Cycle, minute alterations in the world’s orbit, axis tilt, and rotation about its axis. These affect the quantity of solar radiation that reaches the planet, which in turn, controls planetary climatic patterns.

2. Sahara’s Journey Accross the Ocean

Beneath the Atlantic Ocean there are identifiable layers of dust that were blown all the way from the Sahara Desert. Interestingly, the dust contains vital nutrient matter that helps nourishing sea life. This also means that the Sahara once had lush vegetation which has turned into a massive desert over thousands of years.

3. PETM: A Warning from Ancient Warming

Approximately 56 million years ago, the Earth experienced a planet-shattering phenomenon called the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). A fast and extreme global warm-up of the planetary climate. Massive amounts of carbon were released (potentially via tectonic plate faulting/volcanoes, methane hydrates), acidifying seas, causing mass extinction and destroying ecosystems. Shockingly, today’s carbon emissions caused by humans mirror this event; the only difference is that we’re doing it in just under a century.

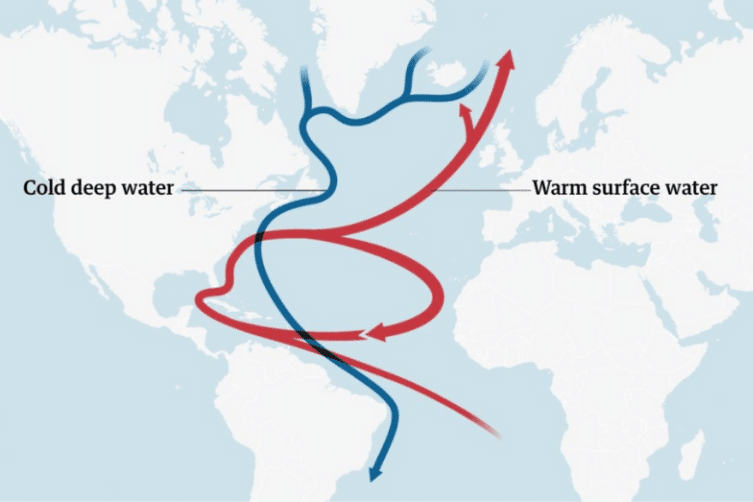

4. The Whirlpool of Ocean Currents

Sediment cores also indicate periods when the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) had become weakened, with catastrophic consequences to European climatic conditions. Scientists today are warning us: if this ocean current weakens again, it will result in unprecedented climate disruptions.

The seafloor may seem quiet but it holds a million stories. Each layer of sediment is like a page in a book, written over many years but preserved carefully over time. By going through these pages, we learn about the past ice ages, deserts, warming events, and ocean currents and thus this knowledge does not remain locked in the past, it becomes a guide for us to understand the present and the challenges that our planet may face in the future.

Leave a Reply